The Semantic Workspace: Augmenting Exploratory Programming with Integrated Generative AI Tools

This is an article complementing the defense of my master’s thesis, generated by AI (ChatGPT) and revised manually. For more details, please check out the slides and the full thesis.

The Nature of Exploratory Programming

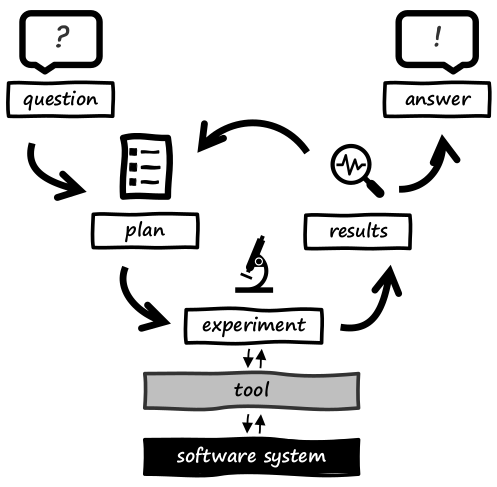

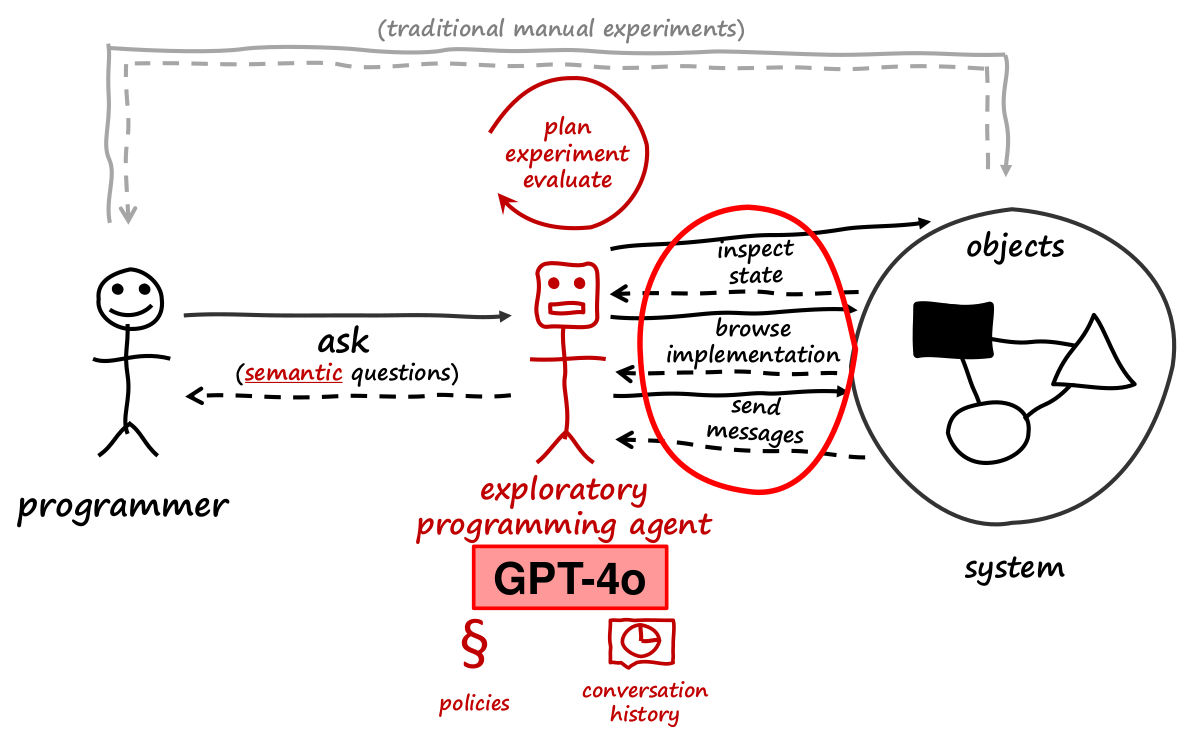

Exploratory programming involves understanding and solving problems while simultaneously familiarizing oneself with the relevant systems and domains. It is an iterative process: we pose questions to the system, plan, conduct experiments, evaluate results, gain new insights, formulate further questions, and move step-by-step toward an answer or solution.

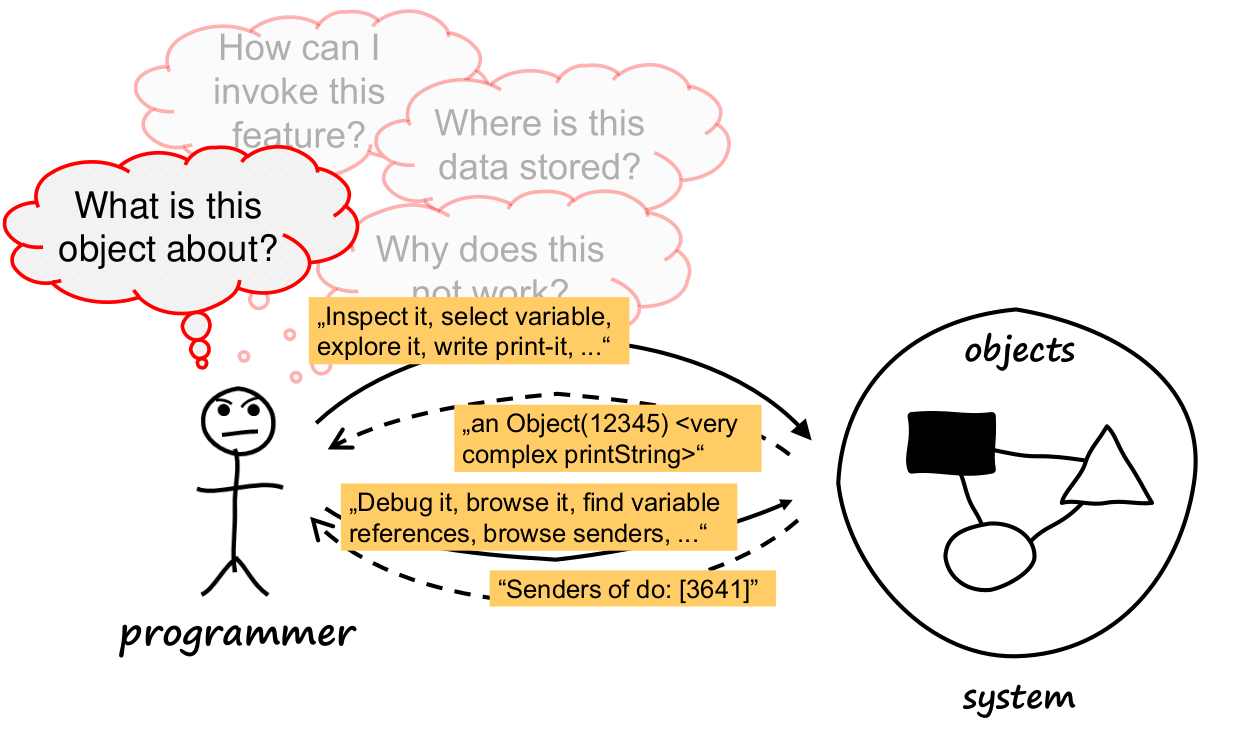

In an object-oriented context, imagine having a programmer and a system composed of various objects. The programmer asks questions about these objects—for example, “What does this object represent?”, “How can I invoke a certain feature?”, or “Why is something not working as expected?” To answer these questions, the programmer interacts with the running system, inspects objects, performs code experiments, and uses various tools such as inspectors, browsers, debuggers, or workspaces.

Challenges in the Current Workflow

This interaction can be quite involved. One must often take numerous small steps, write print statements, open multiple tools, search through source code, or sift through long lists of method senders. The system’s responses—complex print strings, extensive source codes, or large search result sets—are not always immediately clear. Even seemingly simple questions can become unexpectedly complicated to answer.

There are two main technical reasons for these difficulties:

- Conceptual Distances: There is a large conceptual gap between the programmer’s mental model and the system’s technical interfaces.

- Information Overload: A single interaction can yield many and extensive results, such as a large number of method senders or a long class comment.

Combined, these factors make the exploratory process strenuous, time-consuming, and cognitively demanding.

Existing Semantic Technologies and Their Limitations

We already have several semantic technologies in the form of generative AI tools. Large Language Models (LLMs) like GitHub Copilot or ChatGPT are already useful in other programming contexts—for instance, to generate code or answer questions. Embeddings are used to capture semantic similarities between source code or documentation.

However, these tools are currently geared almost exclusively toward static source code. They largely ignore dynamic, runtime information from live systems, the very kind of information prized in exploratory programming. This raises an important question: Why not apply the same AI technologies to improve exploratory programming?

A Vision for Augmented Exploratory Programming

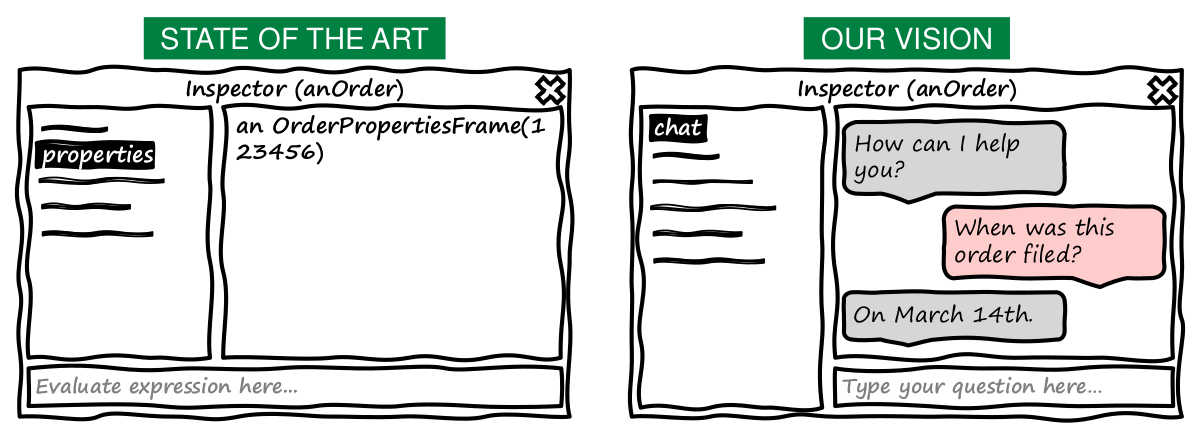

Imagine having an inspector not just as a static tool to view variables and run print statements, but as a tool where you can directly pose conceptual questions in natural language. The system would autonomously conduct the necessary investigations to answer these questions at an appropriate level of abstraction.

This brings us to the central research question: How can we augment the exploratory programming workflow using semantic technologies? The approach is to integrate semantic interfaces into an exploratory programming environment. Programmers can then delegate parts of their work to intelligent agents and collaborate with them. The hypothesis is that this can simplify and enrich the exploratory workflow.

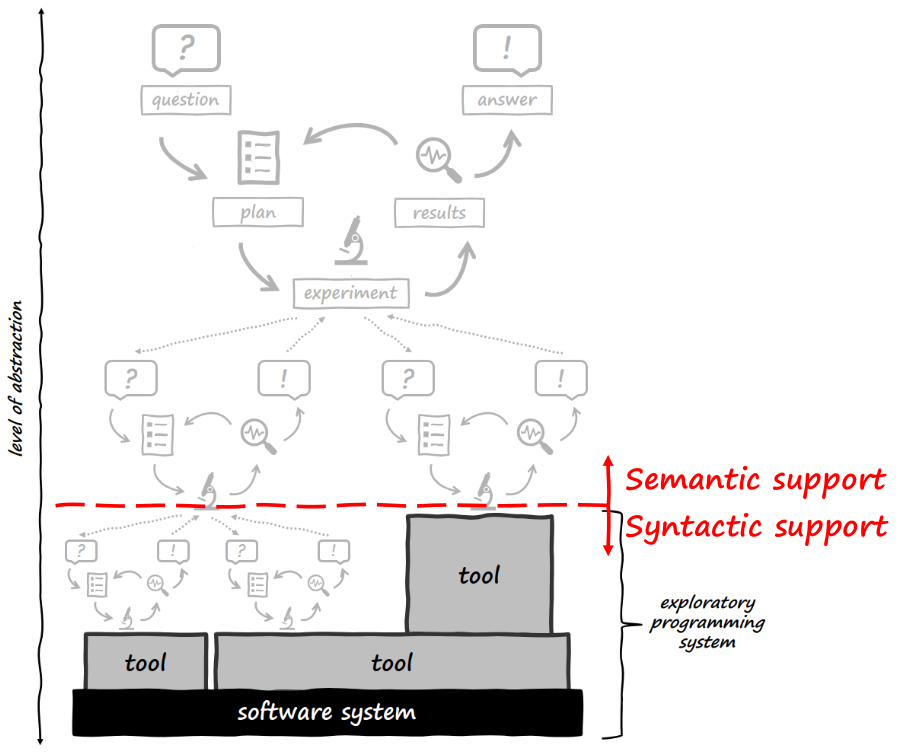

Background: The Iterative Research Process

Exploratory programming is often described in the literature as a process in which programmers understand and solve problems simultaneously and iteratively. Another definition characterizes it as conducting extensive “conversations” with the system, performing many small experiments. From these descriptions, I derived a model of an iterative research process: like researchers, we start with a question, we want an answer, and along the way we must plan, experiment, evaluate results, and iterate if necessary.

A concrete example might be: “When was an order created in a shopping system?” Answering this could involve interacting with various tools such as inspectors and print statements to extract the necessary information from the system.

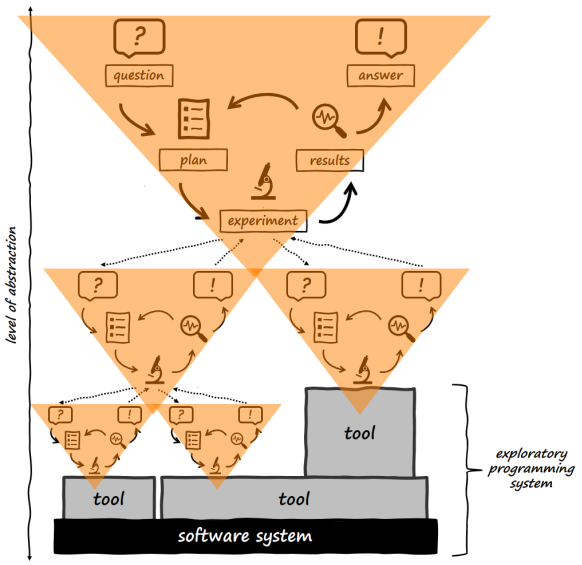

Frequently, the questions we pose are so abstract that no direct tool can provide an immediate answer. Consider the question, “How can I build a suitable UI for this domain?” This leads to further queries like “What capabilities does the UI framework offer?” or “How can I extract the required information from the domain?” The process thus becomes hierarchical and nested, eventually reaching simpler technical questions that existing tools can handle.

Limitations of Today’s Tools

Unfortunately, many parts of this process remain on a high abstraction level beyond what our current tools can handle. Many existing tools are comparatively “dumb,” focusing purely on syntax without understanding the semantic relationships or conceptual questions behind a search or analysis. A standard message-sender tool, for instance, does not know what it means for one method to depend on another; it merely searches for certain literals in bytecode.

As a result, programmers must handle all higher-level, more abstract steps themselves, constantly translating their mental models into technical interfaces and reinterpreting system outputs back into conceptual terms. This is time-consuming, disrupts the programmer’s flow, and often limits the depth of domain exploration. Ultimately, this can affect the quality of insights and solutions.

Leveraging Semantic Technologies in Exploratory Programming

On the other hand, we have semantic technologies that go beyond syntactic analysis. LLMs such as GitHub Copilot or ChatGPT can generate text or code and respond to complex natural-language queries. There are also conversational agents capable of simulating simpler reasoning steps, calling functions, and thus autonomously solving problems to some extent. Embedding models map objects or source code into high-dimensional vector spaces, allowing semantic structuring and searching.

These technologies enable us to move beyond purely syntactic analysis, to ask and answer genuinely semantic, content-based questions. Here lies the opportunity of our work: by integrating semantic technologies into exploratory programming tools, we can enable them to understand the abstract questions and context of programmers and support programmers in higher abstraction levels of there research process.

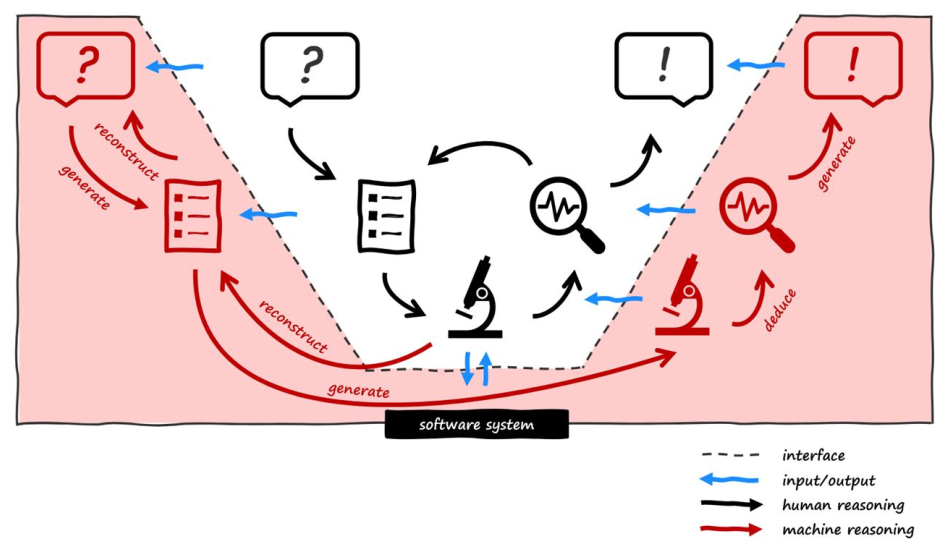

The Concept of Augmented Exploratory Programming

In my work, I call this approach augmented exploratory programming. The basic idea: we still have the classic exploratory process—question, plan, experiment, results, and eventually an answer—but now we envision a semantic exploratory programming system that provides conceptual assistance as well. The programmer can exchange not only concrete experiments but also conceptual artifacts with the system.

For example, the programmer might pose abstract questions or share plans, and the system can respond with appropriate experiments or answers. Internally, the system executes parts of the exploratory process on its own to understand the programmer’s steps, continue them, and continuously provide assistance.

The Semantic Workspace Framework

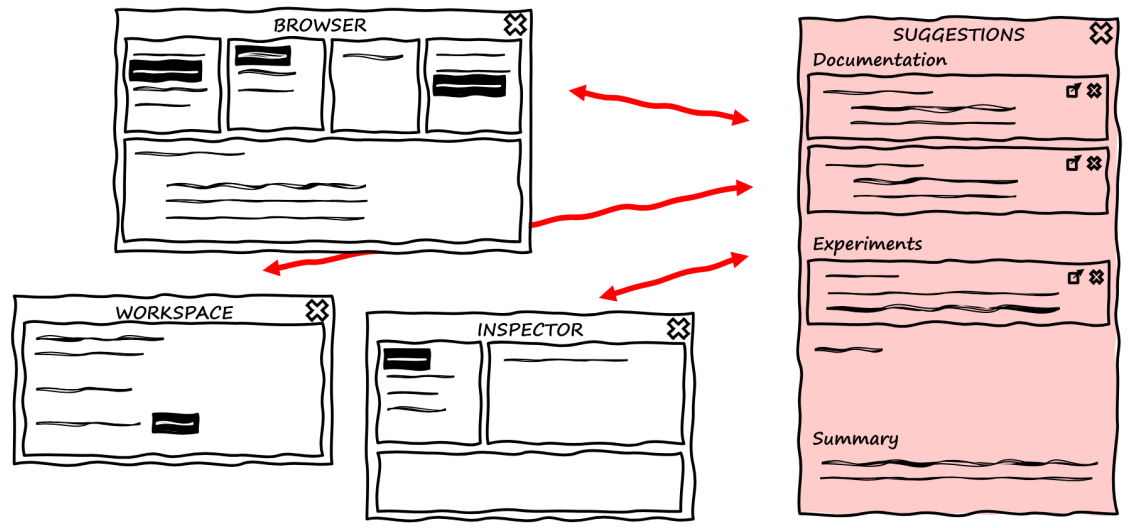

From this idea, I developed the conceptual framework of the Semantic Workspace, an exploratory programming system enhanced by semantic technologies. It provides a spectrum of tools, ranging from more supportive (augmenting) approaches to those that more strongly automate the process:

-

Semantic Suggestions: The system observes the programmer’s actions—what experiments they run, which objects they inspect, which methods they invoke—and suggests further meaningful steps or experiments. Since the system has some understanding of the domain, it can offer more targeted help than a purely syntactic tool.

-

Semantic Completions: Here the system goes further. While the programmer begins writing scripts in a workspace or formulating plans, the system independently performs experiments in the background, summarizes the results, and offers context-aware suggestions on how to proceed. Human and machine intelligence collaborate at an earlier stage of the thought process.

-

Semantic Conversations: This is the most advanced approach and the main focus of this article. The programmer can directly talk to an object in the system in natural language by asking questions such as “When was this order created?” or “How can I extend this UI element for my domain?” The system autonomously conducts the necessary research: it inspects objects, searches source code, executes scripts, evaluates results, and derives a semantically meaningful answer, which it presents to the programmer. The programmer no longer has to manually click through various tools to gather information, as the system provides the required context and details at a higher level of abstraction.

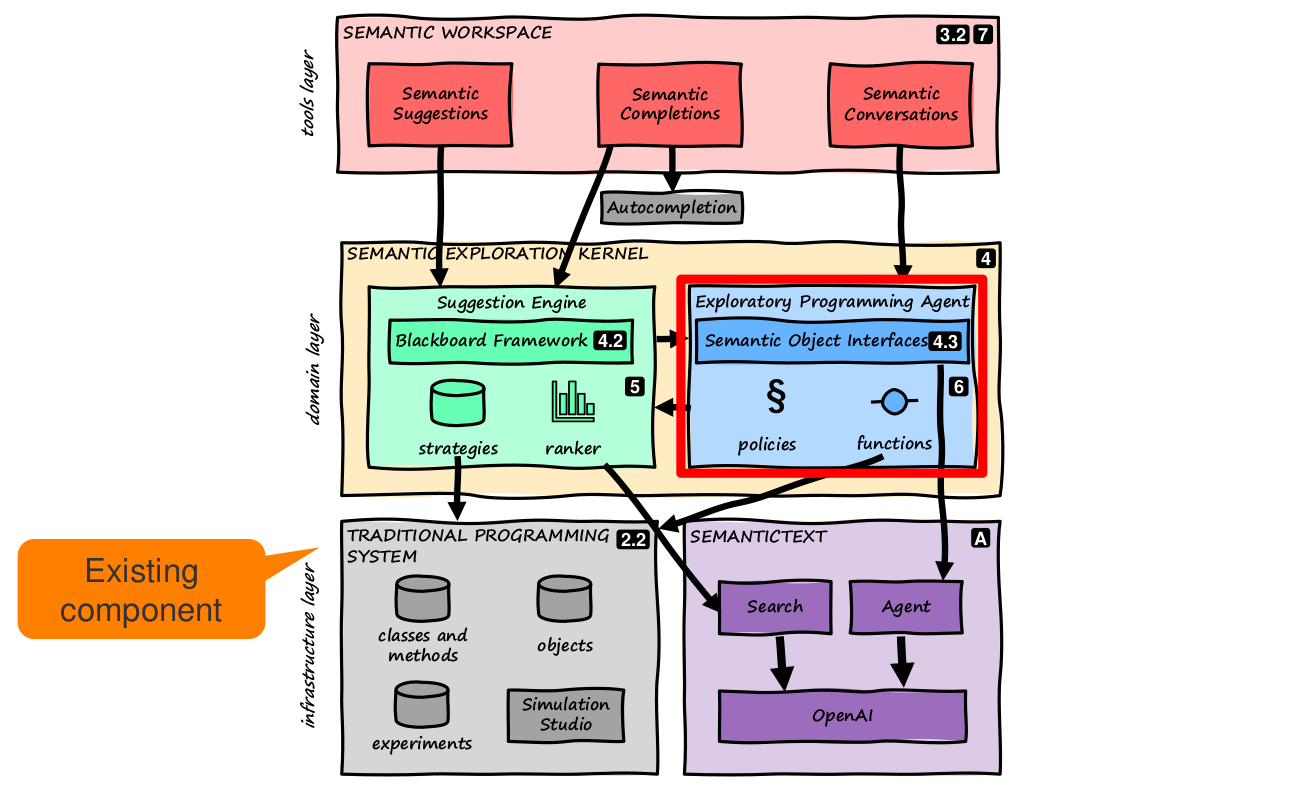

Implementing the Idea: The Semantic Exploration Kernel

To realize these ideas, I built a prototype called the Semantic Exploration Kernel for Squeak/Smalltalk. It is based on the traditional exploratory programming environment (Squeak) and uses my SemanticText framework to access semantic technologies like GPT-4o.

The Semantic Exploration Kernel has two main components:

- A Suggestion Engine for generating suggestions and completions by collecting and evaluating artifacts using certain strategies.

- An Exploratory Programming Agent that offers a semantic object interface between the programmer and the system. This agent translates abstract, conceptual questions into suitable experiments and returns the corresponding answers in a natural-language, understandable form.

To enable semantic object interfaces, the exploratory programming agent is placed between the programmer and the actual objects in the system. It receives semantic questions (e.g., contextual and in natural language) from the programmer, conducts the entire research process internally, and finally returns a semantic answer. Internally, it explores the objects by using existing tools like inspectors, browsers, or print statements. A long prompt and various policies instruct GPT-4o to act as an “exploratory programming assistant.” Access to objects is provided through a facade of existing tools, exposed to the LLM as callable functions.

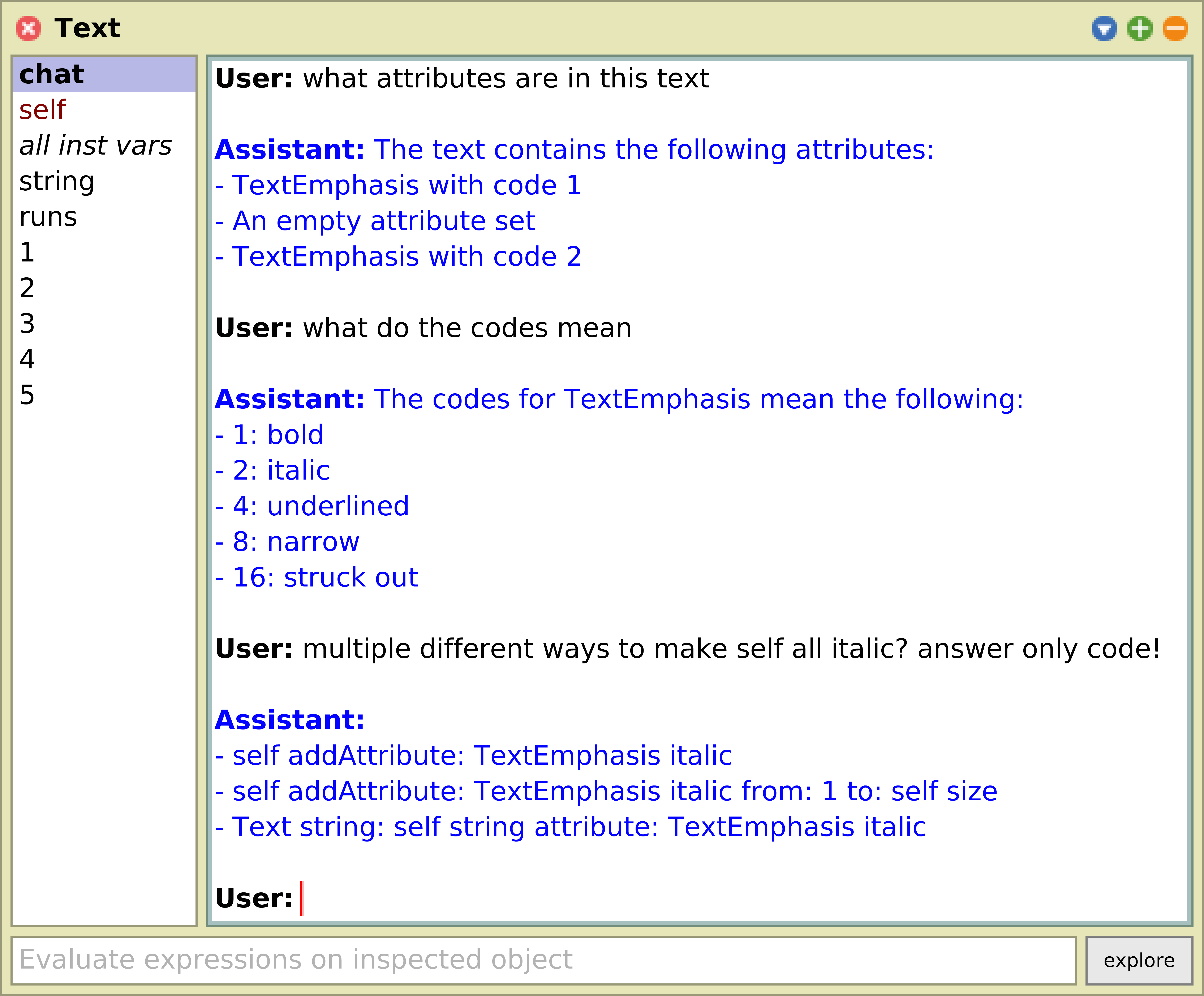

Integrating Semantic Object Interfaces

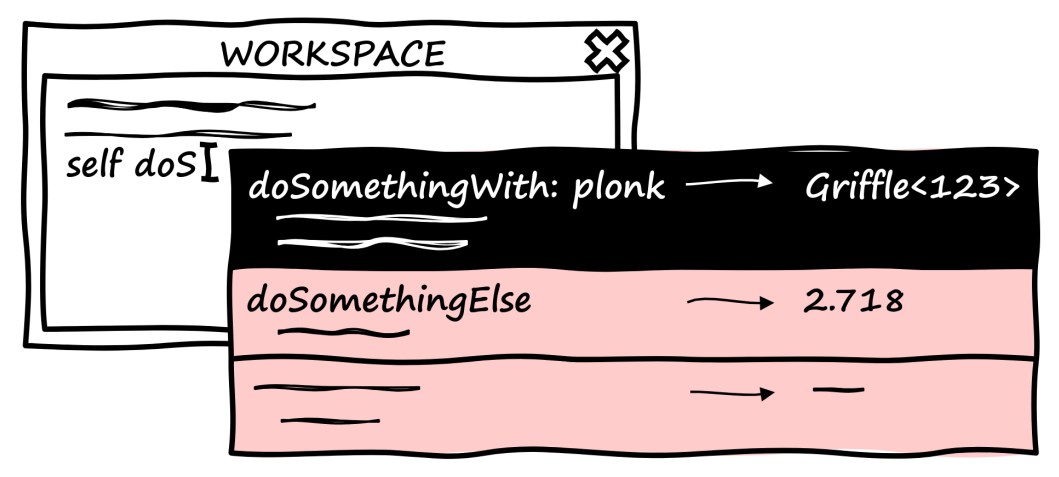

There are different ways to integrate semantic object interfaces into existing tools. One way that I implemented is a conversation mode for object inspection tools: instead of only viewing variables and running print statements, programmers can directly type a question about the inspected object and get an answer from the agent.

Another approach extends scripting: normally, writing print statements requires knowing the exact method names and solving certain algorithmic challenges. With semantic messaging, one can send pseudocode-like messages that semantically describe what is needed. While the domain objects would not understand these messages, the agent handles them and interprets them as questions, conducts the necessary steps, and returns a regular object for further use in the scripting context.

-

Traditional scripting:

aProduct customer lastName. (aProduct orderItems detectMax: #quantity) product. -

Scripting with semantic messages:

aProduct orderItems mostOftenBoughtOne == aProduct mostPopularArticle. aProduct numberOfSalesTo: aCustomer. aProduct countSalesFrom: '2023Q3' to: '2023Q4'.

A Concrete Example

In our example, we are having an Order object in a shopping system and want to know when this order was created. Typically, you would inspect instance variables in the inspector, eventually find a relevant timestamp, convert it into a readable date, and possibly search for relevant methods or classes. This is time-consuming and distracts from the main question.

With the exploratory programming agent, you simply ask in natural language: “When was this order created?” The agent autonomously performs the necessary steps and experiments, then presents the determined date in natural language. You skip all the manual intermediate steps and remain in your mental flow.

We can also use the exploratory programming agent for other exploratory tasks. For example, we use it to explore formatted texts in Squeak, understand how they are modelled internally, and how their formatting can be changed through its interface.

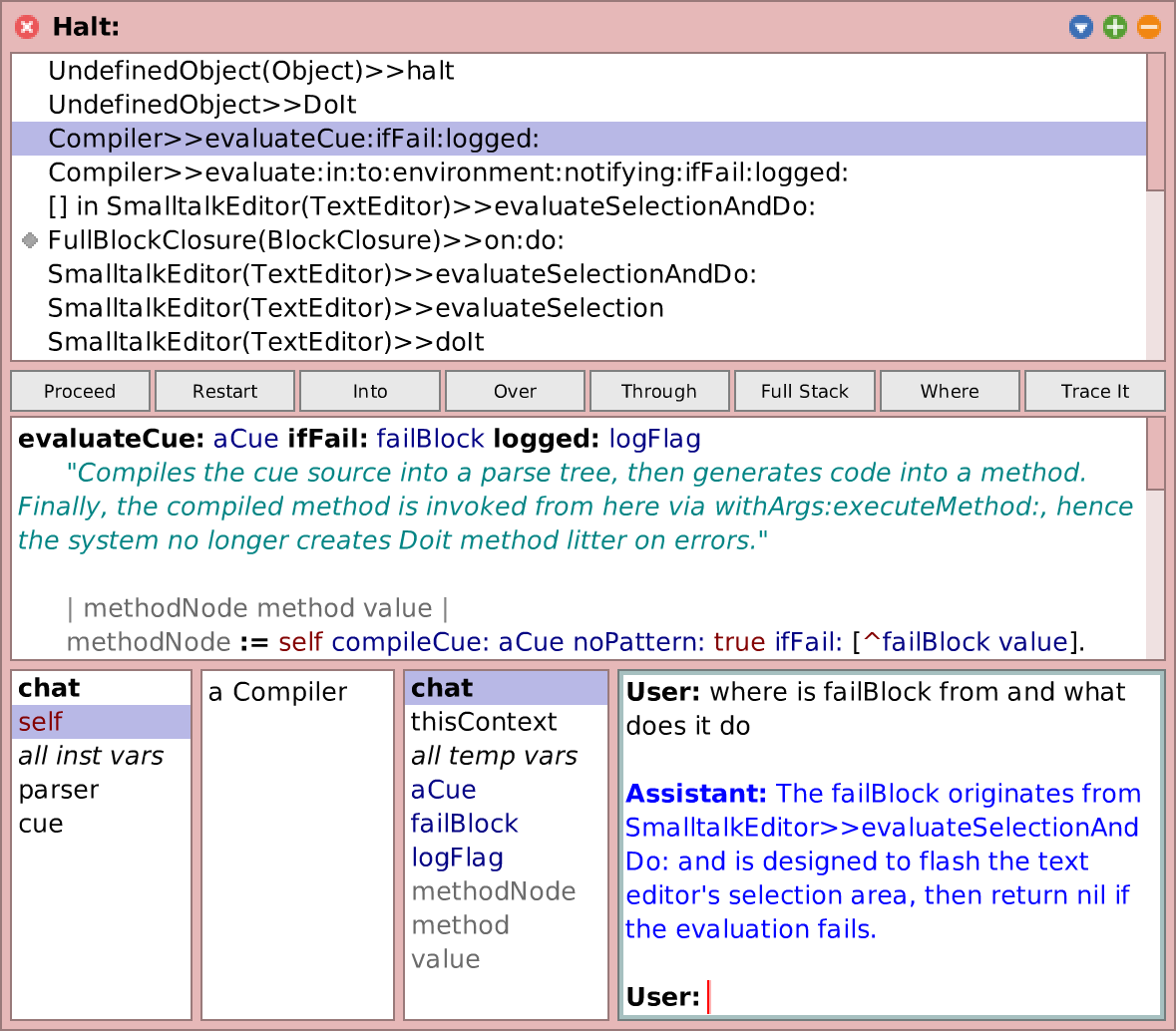

Beyond domain objects, we can use the exploratory programming agents to gain semantic access to existing tools in the system. Since everything is an object, we can also talk to packages, classes, methods; processes and call frames; AST nodes in a method; and so on. This allows us to build different semantic tools with low effort. One example is a semantic debugger where you can ask questions about certain variables in the call stack (“Where does the value of this variable come from?”) instead of manually navigating the entire call stack.

Discussion: Current Capabilities and User Experience

To discuss our work, we investigate two questions:

1. Capabilities of Current Semantic Technologies

Here, we focus on the exploratory programming agent. My prototype based on GPT-4o still has issues. First, it may hallucinate non-existent methods or classes, draw incorrect conclusions, or produce invalid Smalltalk code. Sometimes it fails to complete tasks fully or never terminates. Potential solutions include fine-tuning a model specifically for exploratory tasks and the Squeak/Smalltalk environment.

Second, performance is also a concern: while short questions may have interactive response times, complex queries can take longer and potentially become financially expensive. For example, the above Order example has cost about USD 0.02, but when using semantic object interfaces all the day, expenses in the two-digit range are possible. However, costs are steadily decreasing, and prompt optimization, fine-tuning, and smaller models can likely improve the situation.

2. Impact on Programming Experience

Semantic exploratory programming systems change the experience of programmers in different ways. First, the programmer can remain at a higher level of abstraction, maintain flow, and suffer fewer interruptions. But a kind of tunnel vision may occur: if you get the answer immediately without exploring methods yourself, you may miss out on deeper insights into the class you are dealing with. Natural-language interfaces reduce the gulf of execution and evaluation but can also introduce imprecision. For example, the question “When was this order created?” might be interpreted in multiple ways: date sent, received, or approved?

Delegating more control to the system also demands trust. If the agent makes mistakes, you must be able to trace its steps. Transparency and explainability are thus important topics.

Finally, augmenting and automating tools impact the workflow of programmers in different ways. Augmenting tools integrate seamlessly with the existing workflow and are less radical but offer less far-reaching support. Automating tools like semantic conversations can handle the entire process but pose a “leaky abstraction” risk if the agent fails—then you must revert to manual steps. A balanced combination of augmenting and automating approaches might be best, providing maximum support without overwhelming or disempowering the programmer.

Related Work and Future Directions

The concept is reminiscent of pair programming, except the partner here is an AI. Existing suggestion tools, from traditional code completions to LLM-based completions like GitHub Copilot, already assist with exploration to some extent. Natural-language-based interfaces (e.g., GitHub Copilot Chat) and conversational agents for prototyping or debugging (like Spellburst or ChatDBG) follow similar paths. Tools like Whyline let you assemble debugging questions from a predefined set of building blocks. There are also research efforts into natural language programming (e.g., Navā, GPTScript, or AIOS), where components are controlled purely declaratively or in natural language.

Future directions include training models specifically on Squeak/Smalltalk data to reduce hallucinations and improve quality and performance. A user study could determine whether programmers benefit more from augmenting or automating approaches. Finally, ensuring programmers remain “in the loop” is crucial: we want a scenario where programmers and the AI agent truly collaborate, not one where programmers merely rubber-stamp AI answers. Better explanations of the agent’s steps and results, as well as improved mutual understanding between the agent and the programmer, could foster this collaboration.

Conclusion

In summary, I presented a model of an augmented exploratory programming workflow where a semantic programming system can exchange conceptual artifacts—questions, plans, answers—with the programmer. The Semantic Workspace offers different semantic tools: Suggestions, Completions, and Conversations. I described the design of the Semantic Exploration Kernel, including a Suggestion Engine and an exploratory programming agent, and showcased a prototype for Semantic Object Interfaces. These approaches demonstrate that it is indeed possible to simplify and enrich exploratory programming with semantic technologies.

I would like to thank my advisors Marcel Taeumel, Lukas Boehme, and Robert Hirschfeld for their excellent support and collaboration.